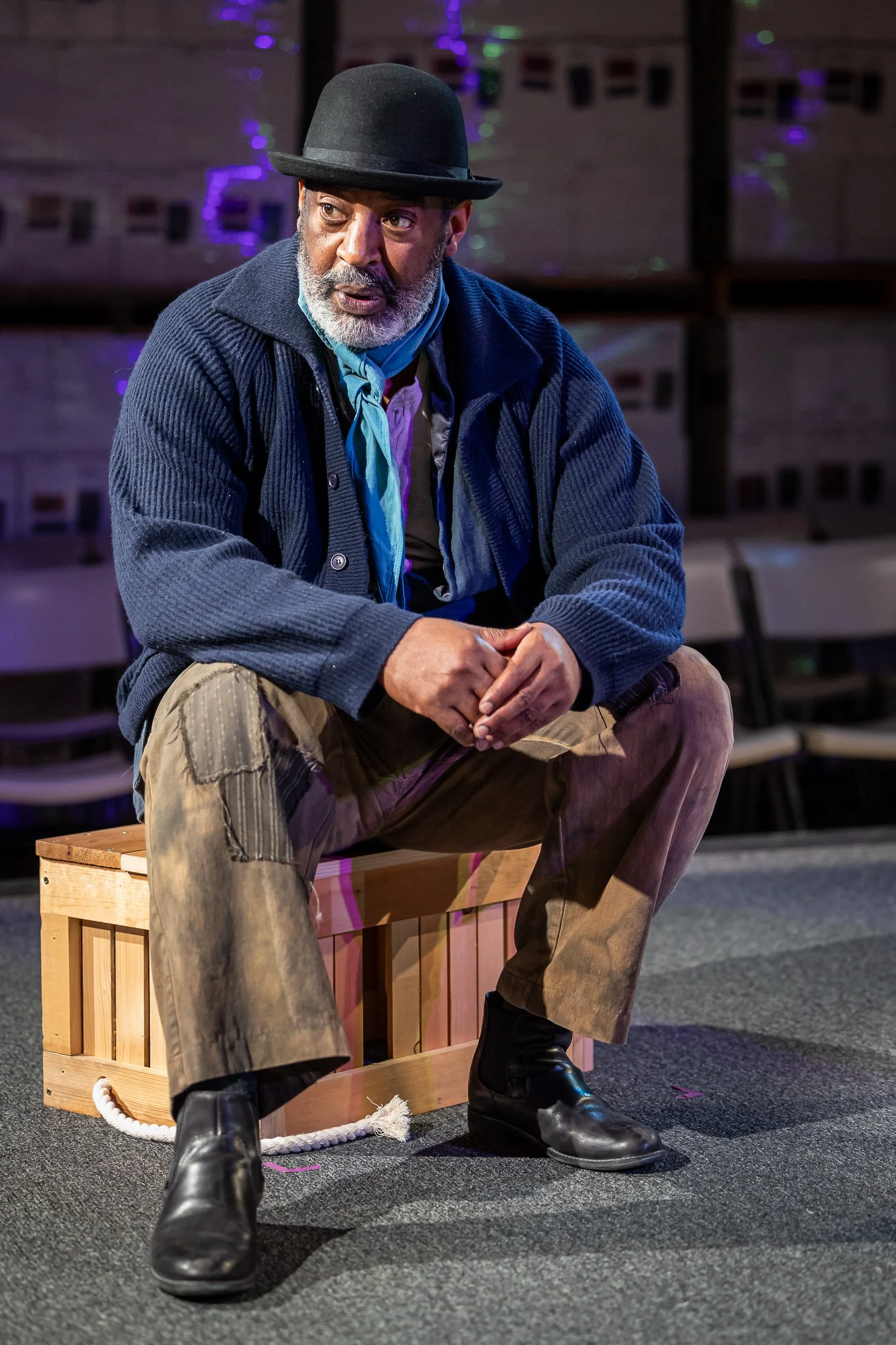

Derrick Lee Weeden

Ray Porter

Jonathan Haugen

Tasso Feldman

Waiting For Godot Review for the Samuel Beckett Society By Geoff Ridden

In a valley full of theatre companies, all of which are dwarfed by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival (OSF), the Rogue Theater Company (RTC) is exceptional. Established by Jessica Sage in 2019, just before the COVID pandemic, the company has not only managed to survive, but has gone from strength to strength, building a reputation for high-quality, professional work.

It has no building of its own, but has established a residency in a winery on the edge of Ashland, in its early years staging plays outdoors on summer afternoons, but, since 2022, offering a full season and moving indoors into a wine storage area, renamed the Richard L. Hay Center. This space lends itself to simple lighting, staging, sets, and props: conditions ideally suited to this play.

Jessica draws upon her extensive list of friends from the theatre world to act in and direct the RTC productions, and many of them are former or current members of the OSF company. All of them are firm favourites with her loyal audience. The cast of this production can boast of fifty nine seasons at OSF between them: even its youngest member (Preston Mead as The Boy) has five OSF seasons under his belt.

The company also specialises in presenting plays with small casts for short runs: their productions have only fifteen performances, in contrast to the Broadway version of the play in the autumn of 2025 at the Hudson Theatre, which featured Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter in its "limited run" of a hundred performances.

This production was staged with the audience on all four sides, very close to the actors. In the centre was a raised octagonal platform which incorporated four sets of steps in its sides. There were two entrances— at the south east and north east corners—and three playing areas: on the platform itself, around the platform and, occasionally, offstage. There was a suspended branch above the stage, and on the platform itself was a crate and an empty metal canister: the set was in other respects quite bare. That circular canister became the mound referred to in the text. It allowed the seated Estragon (Ray Porter) to direct his lines to different parts of the audience with an ease that would not have been possible with a chair.

A reading of the play can give the impression that it is very static, and that nothing happens—twice—but this excellent cast and director demonstrated that this need not be the case. The openness of the set allowed for considerable movement, both on the platform, and around it. Much of that movement was circular (almost always anti-clockwise), giving a sense of entrapment, a centrifugal force from which a character would sometimes break free and be propelled offstage. This escape, however, was always temporary.

The platform was very much the domain of Vladimir (Derrick Lee Weeden) and Estrogen, a territory from which The Boy was excluded: he was confined to the floor outside of the platform. When Pozzo (Tasso Feldman) and Lucky (Jonathan Haugen) appeared, they came on to the platform, but Pozzo had to make a formal request to sit down. Pozzo and Lucky were able to break free from the prison of the circle, by moving diagonally across it in Act One after making a “running start”.

There were many instances in this performance which showed the difference between a reading and a full production, but one which was very evident was the use of ropes. The text certainly refers to ropes but the visual impact of their use is of a different order: we see Lucky (and Pozzo tied together, almost with an umbilical cord, but we are unsure who is in charge, who is making decisions, who is being responsible. Feldman's dapper Pozzo, in riding boots and tight pants, had the air of a circus ringmaster (a circle again), in control only as long as his audience was paying attention to him. The rope intended to restrain Lucky wove all over the platform and much thought must have been given by the director to its journey across the stage: there was no tree to get in its way. And Vladimir and Estragon have a rope too—the rope around Estragon's trousers which would be the rope with which they hang themselves, but it snaps—and yet the break does not liberate them.

In this play characters sit, stand, dance, fall, lie on the ground, help each other or fail to help. Vladimir and Estrogen even strike a yoga pose: all of which activity has to be seen by the audience rather than represented verbally, and requires considerable physical skill on the part of the cast. In this case, they had to rely on themselves and on each other—there were few sound effects and little music.

This is a play about couples. In this production there was a clear physical relationship and an affection between Vladimir and Estragon, in contrast to the dynamic between Pozzo and Lucky, but the parallels between the pairs were very clear. Each couple had Sisyphean tasks endlessly repeated, and their nihilistic world frequently reminded me of the universe of King Lear, not least in the bathos of the failed suicide attempt at the end of this play (which mirrors Gloucester’s attempt to kill himself) and the black humour and cruelty of the jokes about Pozzo’s blindness - “Do we look like highway men?”—recalling the mad Lear’s treatment of the blind Gloucester.

In a production of such overall strength, Lucky’s monologue stood out as a remarkable tour de force, and a welcome departure from its conventional delivery. It was carefully choreographed to fit the actions to the words, and not rushed or delivered in a staccato monotone. Both director and actor deserve great credit for this revelatory moment.

That 1979 production which I saw in England had an all-female cast, and therefore went against the express wishes of the playwright. In the post-show discussion after the first performance of the CTP production, the question of gender was raised, as was the absence of women in the play. This had been touched upon in an article in the Ashland News just before the production opened (October 10 2025) in which reporter Lee Juillerat noted that:

“[some] changes that Rodriguez and Sage thought about taking didn’t happen. As Sage explains, ‘Robynn and I considered casting two women in the remaining roles [of Pozzo and Lucky]. But then came a curveball: A directive from the Samuel Beckett estate declaring there could be no changes to the characters’ genders.’”

Nevertheless, this production was an object lesson in exploring the expectations of masculinity, and the frailties and vulnerabilities of the two central characters. Their complementary voices and the pacing of their repartee also succeeded in melding a convincing informality of language with a sense of the importance of the issues under discussion. That is no mean achievement.

Geoff Ridden taught in universities in England, West Africa and the USA for over forty years. He is also a seasoned stage actor and has narrated audiobooks. Since 2008 he has reviewed the productions of the Oregon Shakespeare Company.